ENHANCING THE VISIBILITY OF INTANGIBLE CULTURAL HERITAGE: THE EMPAAKO TRADITIONAL NAMING PRACTICE IN UGANDA

By Emily Drani, The Cross-Cultural Foundation of Uganda

(see below for the summary in French)

Intangible cultural heritage in the Ugandan context

What is in a name? One might ask. In most African traditions, naming a child is an important symbol of identity and acceptance, and a point of reference for social cohesion. A child’s name usually identifies him or her with a particular family, clan and ethnic group.It is often believed that a child’s destiny will be influenced by the meaning of the name he or she is given. In some communities, names are linked to particular events or circumstances surrounding birth, whether happiness and prosperity or strife and poverty. A name can also recall the reputation of the child’s parents or their aspirations for their offspring. Twins are often given specific names that distinguish them and their parents, while children who are ‘adopted’ by a cultural community are given specific names to denote their relationship with the community. In some communities the naming practice is elaborate, while in others, this could be as simple as a gathering of the immediate family presided over by a paternal or maternal aunt or grandparent.

In 2009, the Government of Uganda ratified the 2003 Convention [1]. Since then, four ICH elements have been successfully inscribed on the Urgent Safeguarding List and efforts are being made to support their viability. This article seeks to demonstrate how an inter-sectoral approach to promote one of these elements- the Empaako naming practice – can potentially enhance its viability and sustainability.

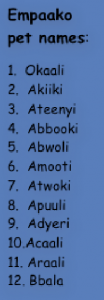

The Empaako is a pet name which affirms one’s social ties; it may be used as a greeting, a declaration of affection, respect, honour or love. Using one’s Empaako underlines social identity and unity, peace and reconciliation. The naming ceremony is often performed in the home, presided over by a clan head. A paternal aunt is responsible for confirming a child’s parentage by examining the baby’s features and resemblance to relatives. Once confirmed, the clan head declares the name to the child, a meal is shared and gifts presented to the baby, including a tree seedling that is planted in its honour. The Empaako practice is found among the Batooro, Banyoro, Banyabindi, Batuku and Batagwenda ethnic groups located in western Uganda. When a child is born, he or she is given one of twelve names shared across all these groups. Besides the parents, the siblings and extended family also witness the naming ceremony and by so doing learn about the cultural values and social significance attached to the Empaako.

In many Ugandan communities, different aspects of culture have remained resilient in the face of the influence of colonial rule, politics, modernity, and religion. Several communities are concerned about preserving their language as an important channel through which their cultures can be transmitted. In many others, social practices, rituals and festive events related to the harvest and cultivation, birth, initiation into manhood or womanhood, and marriage have also maintained their significance. Culture is then often expressed in its entirety, that is, the physical with its associated cultural values and significance, or vice versa. The notion of intangible cultural heritage, with its focus on its social functions and cultural meanings, is not common and is removed from the local understanding of cultural heritage.

Still, culture is often perceived as irrelevant, especially when development is solely measured in economic terms. There are limited avenues through which the Ugandan public can learn to appreciate the value of cultural heritage in a modern context and its potential as a resource for social and economic development. Instead, culture is often perceived as backward and even a hindrance to development. The influences of religions and education that exclude and in some cases demonize traditional cultural ways of life, reinforce these negative perceptions.

Aspects of intangible cultural heritage such as oral traditions and expressions, traditional performing arts, knowledge and practices concerning nature and the universe and traditional craftsmanship suffer in such a situation. The transmission of Empaako through naming rituals has also considerably reduced because of a general decline in the appreciation of traditional culture, religious influences and the diminishing use of the languages associated with the element.

There is however now a deliberate effort to preserve and transmit this heritage to the next generation. To ‘domesticate’ the concept of intangible cultural heritage and to develop practical action to link ICH to sustainable development, a number of local initiatives have been designed.

An ICH and environmental conservation initiative

Since its inception in 2006, the Cross-Cultural Foundation of Uganda, an NGO dedicated to promoting the recognition of culture as vital to human development, has worked with diverse stakeholders using a “Culture in Development” approach. In 2014, CCFU initiated a programme aimed at exploring the link between culture and environmental conservation. This has a particular focus on the role of cultural institutions – traditional kingdoms, chiefdoms, clans and councils of elders – in development, since they have the responsibility of preserving and promoting culture and they are often perceived as gatekeepers and repositories of a cultural heritage in its entirety, among other socio-cultural tasks.

In consultation with the cultural leadership of the Bunyoro-Kitara Kingdom, the Empaako traditional naming practice was identified as an example that illustrates the role of the traditional kingdom in conservation of the natural environment. Working through a management committee composed of community members and Kingdom representatives, 12 forest owners voluntarily offered land on which to plant indigenous trees used for the Empaako naming ceremony. The forest owners developed a heritage plan which included a sensitisation drive on the importance of the Empaako and the establishment of tree nurseries to produce seedlings for free distribution to families performing the naming ceremony. The project received of a small grant from CCFU to implement their plan, monitor progress in a participatory manner, and to enhance the capacity of the community to manage the project.

Along with other gifts, the parents of the new born baby are given a tree seedling to signify new life. This is often the ficusnatalensis, the tree from which bark cloth (which has various cultural functions) is traditionally processed. Other indigenous trees are also grown in the 12 forests and nurseries, contributing to conservation of the environment as well as of the particular tree species. The general public and particularly the youth were sensitized on the importance of the Empaako and associated trees, and 12 schools have been linked to the forests andhave started to plant Empaako trees in their grounds. Women have also been trained in bee-keeping and are now using the 12 Empaako forests to start up an aiary project and plan to brand their honey as “Empaako honey”.

Upon completion of this phase of project, cultural leaders from neighbouring communities were invited to visit the project and share their experience in their role in preserving culture and conserving the environment. The intangible cultural element and how this knowledge is transmitted from one generation to the next were underlined as important aspects of the Empaako practice.

The project attracted unforeseen support. The Kingdom accepted to publicise the Empaako at the Empango, which is the annual anniversary ceremony to commemorate the coronation of the King. Awareness about the Empaako was raised as representatives of other cultural institutions and civil society organisations in and outside the Kingdom in attendance at the empango were exposed to the significance of this practice. A booklet and short film explaining the naming practice and the meanings of the 12 names were produced and widely distributed.

Value attached to the recognition of ICH elements

The process of inventorying and developing safeguarding plans enhanced the community’s sense of self-awareness by drawing attention to their culture as a valuable resource. It highlighted opportunities for cultural tourism, just as tourism has become the country’s main foreign exchange earner. Although the 2003 Convention has remained an ‘invisible’ framework, its underlying objective to safeguard intangible cultural heritage has remained an important thread throughout the project.

As a developing country, with a significant level of poverty, safeguarding ICH must be linked to sustainable development and in this case, the link between the cultural practice Empaako (ICH), the role of traditional leaders in safeguarding the practice and the positive contribution to environmental conservation, has illustrated the potential benefits of synergy between culture and development. Although the community’s primary interest and indeed immediate benefit was not focused on conservation, the project served to heighten the relevance of culture in contemporary development and enhanced community involvement, especially of women and the youth.

This element of intangible cultural heritage also proved to be an effective instrument of community mobilisation. The project attracted the involvement of women and youth who are often at the centre of transmission of cultural knowledge and skills but are rarely visible in safeguarding plans and their implementation. It also enhanced the cultural leaders’ confidence, sense of purpose and contribution to development

Collaboration, synergy and sustainability

The value of partnerships between the community, the cultural institutions and CCFU proved to be crucial. The opportunity to understand the different work ethics and approaches of these different stakeholders provided new learning spaces for all involved and in some cases required reflection and compromise, especially when consultative and ‘bottom-up approaches’ were stressed. NGO operations tend to be project-based and time bound, yet the timing of implementation may be affected by delays due to community commitments, to unpredictable weather patterns resulting in loss of seedlings and requiring replacement.

The project also showed how, if left unguided, the project can take on a life of its own and depart from the initial safeguarding objective. Poverty tends to colour and undermine efforts to enhance social development as communities are preoccupied with their basic survival needs, creating a danger that economic interests overtake the cultural significance of safeguarding efforts.

The 2003 Convention on the Safeguarding of the Intangible Cultural Heritage defines “intangible cultural heritage”, categorises it into different domains and distinguishes it from tangible heritage. On the one hand, the process of inventorying and developing safeguarding plans, broadens and enhances the concerned community’s conceptualisation of their wealth of cultural heritage. On the other, the elaborate and structured process creates the impression that inventorying and safeguarding ICH is essentially an externally driven, technical process that requires external guidance, which is not widely available to local communities and affects their ability to replicate such processes.

Inscription of ICH, and in this case the Empaako, has provided the community with a sense of achievement. The project reinforced the underlying principles of a ‘culture in development’ approach and enhanced the sustainability of the safeguarding efforts. There is however the danger of considering inscription as the end, rather than the beginning of safeguarding efforts. Thus processes that strengthening traditional transmission mechanisms coupled with innovative initiatives are essential. In addition, strategies to ensure that post-inscription activities are implemented and linked to sustainable development initiatives and institutions are essential for the essence of safeguarding ICH to be fully realised.

—————————————–

[1]Uganda, with a population of 38 million and 65 ethnic groups is one of the most culturally diverse countries in the world. While culture is recognised as a source of identity and social cohesion and the need to preserve heritage is acknowledged in the country’s Constitution, the national budget allocation to the culture sector is woefully inadequate at less than 0.003%. The low priority given to cultural heritage stems in great part from a lack of clarity, on the part of policy makers and the general public, of the relevance of culture to the country’s development challenges.

_____________________________

Favoriser la visibilité du patrimoine culturel immatériel

L’empaako, pratique traditionnelle d’attribution du nom en Ouganda

(Translation by Séverine Cachat)

Résumé

Dans la plupart des traditions africaines, l’attribution du nom à un enfant est un symbole important d’identité et d’intégration sociale. Depuis 2009 et la ratification par le gouvernement ougandais de la convention de l’Unesco sur le patrimoine culturel immatériel, quatre éléments du PCI ont été inscrits sur la Liste de sauvegarde urgente, et des mesures ont été adoptées pour maintenir ces éléments vivants. Cet article cherche à démontrer en quoi une approche inter-sectorielle de la promotion de l’un de ces éléments – la tradition de l’empaako – peut favoriser sa survie dans le temps et son dynamisme.

L’empaako est un système d’attribution de nom pratiqué par les populations Batooro, Banyoro, Batuku, Batagwenda et Banyabindi, qui consiste à attribuer aux enfants l’un des douze noms communs aux communautés en plus de leur prénom et de leur nom de famille. Le fait de s’adresser à quelqu’un par son nom empaako est une manière de souligner les liens sociaux, et de favoriser l’unité, la paix et la réconciliation. Dans beaucoup de communautés ougandaises, certains aspects de la culture ont mieux résisté que d’autres à la domination coloniale, aux décisions politiques, à la modernité et à la religion. En ce qui concerne l’empaako, sa transmission par les rites d’attribution du nom s’est considérablement affaiblie, en raison du déclin général de la culture traditionnelle, de la diminution de l’usage des langues associées à cette pratique, et des influences religieuses grandissantes.

En 2014, la Cross Culture Foundation of Uganda (CCFU) a engagé un programme d’étude du lien entre culture et préservation de l’environnement, programme qui s’intéresse notamment au rôle des institutions culturelles, souvent perçues comme des gardiennes et dépositaires de l’héritage culturel dans sa globalité. Après un travail d’analyse en partenariat avec la direction culturelle du royaume Bunyoro-Kitara, il a été établi que l’exemple de l’empaako illustrait le rôle du royaume traditionnel dans la préservation de l’environnement naturel. Douze propriétaires de forêts ont développé un projet patrimonial alliant une campagne de sensibilisation sur l’importance de l’empaako et la plantation d’une pépinière d’arbres, destinée à produire des plants distribués gratuitement aux familles pratiquant la cérémonie d’attribution du nom. Le projet a reçu une subvention de la CCFU pour permettre sa mise en oeuvre, son suivi et l’accompagnement de la communauté dans sa gestion participative. Les femmes ont également été formées à l’apiculture et utilisent à présent les douze forêts empaako pour produire un miel vendu sous l’appellation “miel empaako”. Le lien avec le patrimoine culturel immatériel, et la façon dont cette connaissance est transmise d’une génération à l’autre, ont été soulignés comme des aspects très importants de la pratique de l’empaako.

Le projet a mis en évidence des opportunités pour le tourisme culturel, au moment où ce domaine économique est devenu l’activité la plus rentable du pays. Le rôle des dirigeants traditionnels dans la sauvegarde de l’empaako et sa contribution à la préservation de l’environnement ont montré les bénéfices potentiels d’une synergie entre culture et développement. L’inscription de l’empaako a procuré à la communauté un sentiment d’accomplissement. Le projet a renforcé les principes sous-jacents d’une approche du « développement par la culture », et a amélioré la durabilité des efforts de sauvegarde.